In April, the Environmental Protection Agency proposed strict Phase 3 greenhouse gas (GHG3) regulations for heavy-duty vehicles in a bid to increase the number of zero-emission trucks on the road.

The ATA shares the goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions and improving fuel efficiency, and our members continue to make the necessary investments to support a decarbonized future. We believe any regulation must be:

✅Technology neutral

✅Achievable

✅Based on sound science

Unfortunately, GHG3 does not meet any of these standards.

A survey of our members revealed the enormous hurdles and complex challenges that motor carriers are facing as they manage the transition to a zero-emission future while simultaneously moving more than 72 percent of the economy’s freight. Based on this member feedback, ATA has engaged in the regulatory process and submitted comments to urge the EPA to go back to the drawing board to ensure its regulations are technologically feasible.

Our comments identify seven significant transgressions that GHG3 commits against the supply chain. Unless the EPA atones for these errors, severe economic disruptions are sure to follow.

1. Reneging on GHG2

The trucking industry has a long history of working collaboratively with the EPA and adopting the cleanest emissions technology on the road today. That is why the ATA is extremely disappointed that EPA has chosen to reopen the established GHG2 regulation. Setting new emissions standards for 2027-2030 pulls the rug out from under manufacturers and fleets, upending purchasing plans and limiting product availability.

Solution: EPA should not reopen GHG2 standards for 2027, which represent years’ worth of stakeholder discussions, input, data sharing, and negotiation.

2. Ignoring Alternatives

EPA’s proposed GHG3 regulation leaves fleets with the choice of battery-electric or hydrogen fuel cell, overlooking other readily available low-carbon fuel options using more cost-effective assets.

Solution: EPA must adopt a fuel and technology-neutral approach that incorporates established low-emission fuels. Including more mature and available fuels like renewable diesel, biofuels, compressed natural gas, and clean diesel can effectively reduce emissions today and align with the operational profile of our industry.

3. Creating Instability

In the past, EPA regulations have aligned with the truck model refresh cycle, providing regulations covering three years of manufacturing. Under GHG3, however, new heavy-duty emissions standards would be set each year starting in 2027. Consequently, there would not be sufficient time to test and evaluate new technologies before they start hitting the road.

Solution: GHG3 stringency targets should not begin until model year 2030 at the earliest to allow EPA time to evaluate the technology and give fleets and OEMs the ability to gather more real-world data.

4. Gambling on New Technology

EPA’s analysis assumes reductions in battery and vehicle costs, performance, energy generation and transmission, and charging and refueling infrastructure. But the evidence for these rosy predictions is thin.

In their responses to ATA’s survey, fleets worried that capacity improvements in batteries or efficiency gains will not necessarily translate into direct price reductions in the near to medium term. Notably, battery and component costs have remained comparatively stable for light-duty electric vehicles. One fleet shared it had actually seen prices increase year-over-year due to component pricing.

In order to be a practical alternative to clean-diesel trucks, zero-emission trucks must also be capable of carrying the same payload while climbing steep inclines, maintaining speeds on highways, and handling challenging extreme temperatures.

Solution: More research and testing are needed to prove that the technology can scale to meet the trucking industry's various duty cycles and operating environments.

5. Imposing Spendthrift Procurement Policies

The upfront acquisition costs for zero-emission vehicles are generally much higher than clean-diesel vehicles. Before incentives, costs can be two to three times higher for battery-electric vehicles and up to seven times higher for hydrogen fuel cell Class 8 trucks.

Under GHG2, the payback period for a tractor is 2 years for 2027 models. Under GHG3, this payback period would skyrocket to 8 years. These figures account for the IRA vehicle tax credits, which sunset in 2032. Absent these credits, the payback period would be 14 years.

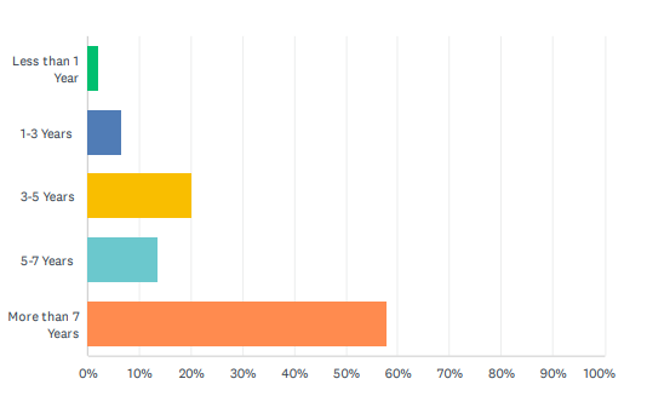

Most motor carriers that responded to ATA’s survey believe the payback period for a zero-emission truck would be at least 7 years. If fleets do not see the expected return on investment, they will likely hold onto their existing equipment longer, resulting in older trucks on the road with much higher emissions profiles.

Expected Payback Periods for ZEV Technology

Solution: A crediting system that prorates the annual expansion of lower carbon fuel use across new conventional vehicle sales is needed to capture existing carbon reduction efforts. This system would help account for fleet efforts to purchase conventional or alternative fueled vehicles rather than only zero-emission vehicles.

6. Neglecting Infrastructure

EPA claimed there are federal funds available to states to support the construction of charging networks under the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and the Inflation Reduction Act, but these laws focus on charging for light-duty vehicles, not heavy trucks.

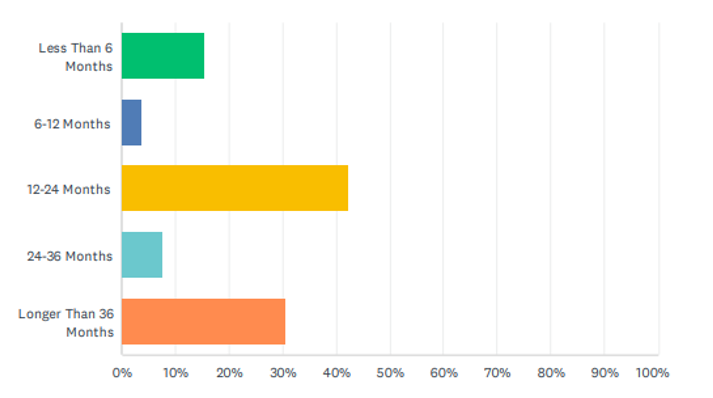

Moreover, ATRI estimates full commercial vehicle electrification would require a 14 percent increase in energy generation from today’s standards. In many cases, remote or densely populated areas do not have available power to direct toward commercial vehicle charging sites. One fleet told ATA that their plan to fully electrify just their forklifts was stymied because the local utility could not provide sufficient power. Among surveyed fleets, 30 percent were informed by their local utilities that they would require at least 3 years to provide onsite charging.

Currently Quoted Lead Times for Onsite Charging

Solution: EPA must develop a detailed plan for the robust buildout of heavy-duty charging infrastructure and energy transmission.

7. Exacerbating Driver and Technician Shortages

In 2022, the truck driver shortage remained near its historical high at nearly 78,000 drivers. Qualified technicians, especially ones with advanced electrical training, are also in short supply.

Some fleets have indicated that the range limitations, charging times, and increased weight of zero-emission trucks will require two trucks to do the same amount of work as one truck. These factors can potentially worsen the driver and technician shortage as well as increase congestion on highways and at ports.

Solution: EPA must broaden its analyses and quantify the impacts of GHG3 regulation on driver operations and the industry’s overall efficiency.

Bottom Line

ATA members have made significant environmental progress in adopting emissions technology that has reduced criteria pollutants by 99 percent and cut oil consumption. Our industry has supported past EPA regulations because they were achievable and benefited fleets with reasonable payback periods for emission reducing technologies.

Under GHG3, the EPA would require industry to adopt yet to be proven technology, without sufficient charging or refueling infrastructure to support proposed adoption rates and abandon the collaborative trust by reopening GHG2 standards.